CNN Business reported that the coronavirus could cost China’s economy $60 billion.

That’s due to missed trade opportunities and work, but that’s the power of networks.

Few people or countries achieve greatness alone.

Hunters and gatherers society was rough–we spent much of our time isolated, constantly working for the minimum to get by.

Networks are similarly to trade; countries specialize in what they do best and then exchange currency, goods, and services.

For example, Turkey is the world’s largest exporter of cherries.

Turkey increased cherry juice concentrate exports into the United States from 24 million pounds in 2008 to more than 200 million pounds in 2016, according to the DeWitt-based Cherry Marketing Institute.

U.S. total exports of agricultural products to Turkey totaled $1.4 billion in 2018, with cotton ($682 million), tree nuts ($279 million), and distillers grains ($191 million) seizing the top spots.

That’s why grocery stores have 30 separate kinds of cereal. Trade allows so much mutual benefit that most people in developed countries don’t rely on the bare minimum to get by.

Walmart operates in at least 27 countries, and most stores sell products that originated across the world. It’s similar to big cities offering cuisine from across the world.

Networking with people isn’t much different; it’s mutually beneficial to reap benefits from the talent of your friends.

That’s what happens when you know a bartender or bouncer and pay half of the regular drink price or skip cover.

Pirates are a great example.

Contrary to popular belief, all pirates weren’t bloodthirsty barbarians. Historian Sara Whitford says there’s no record of Blackbeard ever killing someone.

But pirates wanted a savage reputation, so they shared gruesome tales whenever they docked, which spread.

It was a smart play; it’s easier to rob ships peacefully if the victim believes the pirates are maniacs–most wouldn’t even fight back.

But they weren’t.

Pirates operated democratically, with the captain only taking full control in emergencies. They even offered compensation for pirates hurt during raids, according to George Mason Economist Peter Leeson, and shared information, giving them the power to gather information from across the sea.

Hurt and maimed pirates meant that individual pirates received less profits, so it was in their best interest to keep raids as nonviolent as possible.

Don’t get me wrong: pirates were thieves, and I can’t condone coercion to force involuntary trade. But although goods were pilfered, many those people returned to their families.

I’m just analyzing the method by which a group of people spread disinformation so successfully that most people today still think pirates were barbaric.

Companies act similarly today to hedge risk for worker’s compensation or settling a lawsuit before it reaches trial.

When Venmo growth exploded as younger generations used less cash, the company dented Paypal’s profit.

So Paypal bought Venmo for $800 million in 2014 and raked in $9.2 billion in revenue in 2015 (they own multiple companies, which also hedges risk).

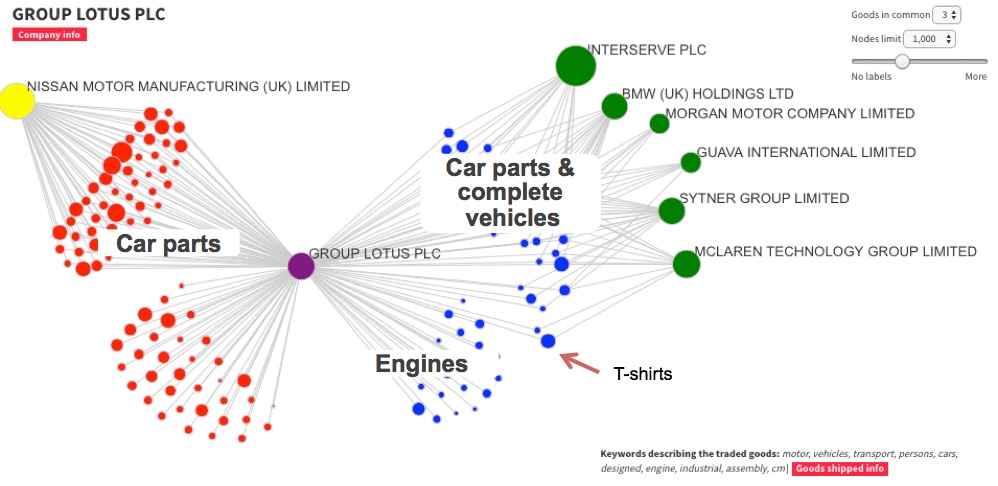

Networks essentially allow one to clone themselves, pulling information and talent from across international industries.

Consider marijuana dispensaries in the United States. For a dispensary to be successful, customers must be able to access their location, know about them, and make a separate trip from groceries and gas.

Moreover, dispensaries have high overhead cost and are mainly cut off from banks, forcing them to operate using cash, not credit.

But across the pond in Europe, medical marijuana is sold in pharmacies, slashing many problems facing dispensaries in America.

Just one major pharmacy obtaining a license to sell marijuana could ease access in every state if the plant were de-scheduled on a federal and state scale.

Then customers could pick up milk, meat, and marijuana in one trip.

That’s the power of networks.